Press release -

COMMENT: Slash fiction, cosplay and Sherlocked: a guide to fandom

Dr Claire Nally, Northumbria University, Newcastle, discusses fan culture and slash fiction.

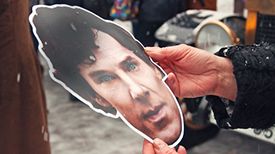

If you were to find yourself in a particular corner of east London in the last weekend of April, you might come across an unexpected event. The ExCel Centre is hosting the official Sherlock fan convention, and so a host of cast and writers will assemble there amongst hundreds of eager fans to immerse themselves in the world of the famous detective. Tickets range from £29 to an astonishing £2995, which includes a photo shoot of you with each of the attending guests. Evidently that’s a bargain for some – after all, you get a snap with Benedict Cumberbatch.

It certainly might seem as if fan culture has reached a whole other level recently. The BBC recently got Tom Felton (aka Draco Malfoy) to travel round the US meeting “the superfans”. The outcry at Zayn Malik’s departure from One Direction dominated Twitter. Some of the biggest blockbuster books and films started out as fan fiction (think: 50 Shades of Grey).

So what is it that underpins fan cultures? Avid followers of books, TV shows, films (and One Direction) engage with their source material in a number of ways. “Fanfic” rewrites and reimagines the original text – and online communities debate, explore and share opinions and self-penned stories. Then there’s cosplay, where fans assemble at conventions and other social events to perform the role of a favourite character, usually through costume and accessories.

Old tales

Fan culture proliferates by avoiding the traditional methods of publication: through zines, online forums, and self-published ebooks. The internet may have provided an infinite new platform for fan cultures and fan fiction, but even if they seem increasingly pervasive, they are far from a new phenomenon, as Anne Jamison has observed:

In various ways, fan fiction resembles all storytelling, ever. People like to swap stories, period, and the internet is like a big electronic campfire.

Borrowing material from other authors to create stories is nothing new. In the 18th century, writers such as Alexander Pope thought careful emulation of the classics was the highest demonstration of literary talent.

Fan cultures also predate electronic communication systems like the internet. In some ways, Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) and his Sherlock Holmes series spawned one of the first fandoms. While Doyle himself saw Sherlock Holmes as a fairly disposable character, his readers thought otherwise.

Holmes quickly became immensely popular with readers – and so when Conan Doyle decided to end his character’s career with a plummet to his death from the Reichenbach Falls (in The Final Problem, 1893), there was a massive public outcry. Men in London were seen sporting mourning crepe in their hatbands in honour of their beloved detective – we could see this as a form of proto-cosplay. In America, fans formed “Let’s Keep Holmes Alive” clubs. The pressure from publishers and fan readers resulted in Conan Doyle resurrecting Holmes ten years later.

Slash fiction

Move on 120 years, and fandom has grown exponentially. One particular variation on fanfic is commonly known as slash fiction: this is a genre where writers borrow characters from their favourite shows and pair them in homoerotic scenarios. For instance, we might read of romantic liasions between Frodo and Sam from Lord of the Rings, or in Sherlock fandom we have the Cumberbatch/Freeman duo, in a slash fiction gesture commonly known as Shwatsonlock.

Interestingly, it’s most often women who write slash fiction. Some have seen slash fiction as a radical gesture – seeing it as a form of “guerilla erotics” that seeks to challenge literary paradigms and tropes in a way that more mainstream material does not. We can see it as a challenge to mainstream stereotyping: the homoerotic partnering emphasising affection and intimacy between two male characters, rather than the convention of promiscuity and shallow encounters which popular culture often problematically associates with homosexuality.

But more recent debate has challenged this idea of radicalism, aligning slash fiction with more traditional forms of romance fiction such as that published by Mills and Boon. Slash prioritises love and partnership, imagining not one but two men who express their feelings in ways that other forms of erotica might neglect. For many women, this is an important outlet. The author of the fanfic that Caitlin Moran got Cumberbatch and Freeman to read out in interview hit back at “fanshaming”, saying: “Thank you for tainting the one thing sometimes that gets me through the day.”

Fandom may provide an important place in which many find solace. But the ethics of such internet forums are somewhat fraught. Amanda Abbington (Watson’s on-screen wife, who is also married to Martin Freeman) recently received widespread abuse and death threats after she criticised fanfic slash pairings involving her husband and Benedict Cumberbatch. It’s important we speculate how far fandom (or indeed the internet as a whole) is, in the end, sympathetic to women.

Regardless, the genre continues to evolve. We now have fanvids, too. Here’s a particularly good example of the Sherlock/Watson pairing, using clips from the TV show and a poignant backing track from Florence and the Machine, adding an emotional depth to the Sherlock/Watson relationship which hinges on “bromance” much more than the Sherlockian convention of rational detection.

It will be fascinating to see how this sub-genre in particular develops when Sherlock returns to our screens.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Categories

Northumbria is a research-rich, business-focussed, professional university with a global reputation for academic excellence. To find out more about our courses go towww.northumbria.ac.uk

If you have a media enquiry please contact our Media and Communications team at media.communications@northumbria.ac.uk or call 0191 227 4571.