Press release -

COMMENT: Hoax calls to the PM are the price we pay for democracy

Professor Howard Elcock, examines the pros and cons of open democracy

The ease with which a hoaxer was recently able to call the prime minister’s mobile phone, pretending to be the head of GCHQ, highlights a major dilemma for democratic political leaders. Cameron said he quickly realised the call was a fake and hung up immediately. He has also said that no security was breached and no harm was done.

But in a knee-jerk response, there have been calls for the PM’s security to be tightened. This is not a sufficient or entirely appropriate response. Citizens must have the right to access their leaders. It’s a right that dates back at least to the fifth century BC and Pericles, who addressed the Assembly of Athens frequently and in person. Personal accountability is an essential component of democracy.

In a democratic political system, the public must have the right to approach its government. Voters need to be able to demand the redress of their grievances and to pursue their aspirations for a better life.

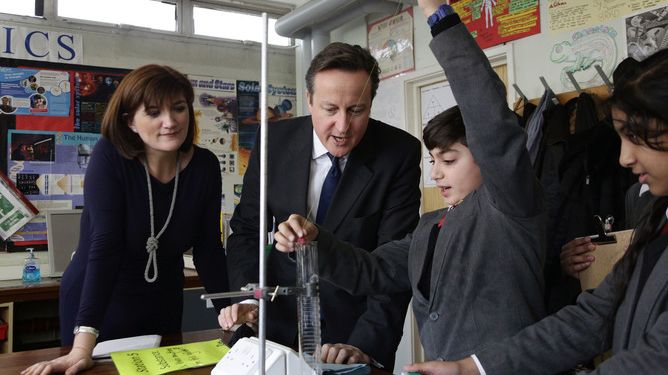

In the British parliament this necessity is underlined by the requirement that all MPs, regardless of their rank or power, must meet regularly with their constituents and try to address the problems those constituents bring to them. Even being prime minister does not excuse David Cameron from holding constituency surgeries and dealing with correspondence from those constituents.

In this respect, the UK system is different from other countries such as France, where government ministers give up their seats in the National Assembly to substitutes and become totally absorbed in the administration of their departments. That may be more efficient but you might question whether it enhances democratic accountability.

Take the rough with the smooth

There are obvious dangers in being prime minister, ranging from a possible terrorist attack to being pelted with eggs or rotten tomatoes at public meetings. But protecting the PM and his or her ministerial colleagues from danger or nuisance must not deny them frequent and easy contact with citizens.

In the Labour years, Tony Blair did a good deal to widen public access to Number 10 by opening up a website for the public to communicate with him. He also introduced the rule that if an electronic petition attracts enough signatures, it can trigger a debate in parliament.

In this respect, it has never been easier to exercise the rights and duties of the citizen as defined by Aristotle – to participate in the government of your community. It is good that it should be so and the citizenry must be encouraged to participate actively in their government using all the means now available to them.

But none of this – no online petitioning or website browsing – can be a substitute for citizens being able to access the prime minister and other office-holders.

Research at Northumbria University and elsewhere has demonstrated that elected mayors highly value their direct contact with local citizens. Be it by mail, telephone or in the streets, they see dealing with requests and complaints from citizens as an important part of their job.

Prime ministers and their colleagues must feel and do the same. If the price for giving citizens proper access to their leaders is the occasional hoax, confrontation or other security lapse, this cost must be accepted as part of the job.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Categories

Northumbria is a research-rich, business-focussed, professional university with a global reputation for academic excellence. To find out more about our courses go towww.northumbria.ac.uk

If you have a media enquiry please contact our Media and Communications team at media.communications@northumbria.ac.uk or call 0191 227 4571.