Press release -

COMMENT: What would a U-turn on academies do to Conservative education policy?

Michael Jopling, Professor in Education, Department of Education and Lifelong Learning at Northumbria University, discusses academies for The Conversation.

These are testing times for the government’s education policy. The purported U-turn on its plans to force all schools in England to become academies by 2022, outlined in a recent education white paper, may or may not come to pass. Either way, the current furore about the plans among Conservative supporters and party members is likely to have long-lasting repercussions.

Despite politicians’ claims to the contrary, education policy has rarely been based or even informed by evidence. Many have expressed concerns about the lack of clear evidence that forcing schools, especially primaries, to become academies will have a positive impact on children’s learning.

A recent report sponsored by the Local Government Associationsuggested that many local authority schools outperform academies. This prompted a remarkably ill-tempered response from the Department for Education, which suggested that they are feeling the pressure.

Others have speculated about why the government has persisted with such an unpopular and controversial policy.

Unprecedented criticism from within

Conservative school policies since the Thatcher administrations of the 1980s have had a number of familiar strands. Among the most consistenthave been increasing competition between schools, increasing choice for parents and students, and decreasing the power of local authorities, even in the face of popular opposition.

But it is difficult to think of education policies which have engendered the kind of grassroots revolt among Conservative supporters that the forced academisation plan has brought about.

But it is difficult to think of education policies which have engendered the kind of grassroots revolt among Conservative supporters that the forced academisation plan has brought about.

John Patten, John Major’s education secretary between 1992 and 1994, described himself as “having tried to restore power to the centre, wresting it back from Local Education Authorities and redistributing it to schools”. He did this through the grant-maintained school policy, which was in many ways the forerunner of the current academy programme.

That government did not come anywhere near meeting his target of making all schools grant-maintained by 1997. The introduction of a voucher scheme, which the Conservative party had regarded as unworkable in the 1980s, suffered a similar fate when it was controversially applied to nurseries in 1996 in the form of vouchers for parents of four-year-olds to use in providers of their choice.

Although some councils rebelled against the voucher scheme, both policies largely retained party support even as the Major government declined. The election of the New Labour government in 1997 ended both initiatives.

Implications for Tory education policy

Conservative education policies since 2010 have explicitly shifted power from local authorities to the political centre while at the same time portraying this as supporting localism and increasing school autonomy. This has been widely criticised by opponents for some time.

The difference now is that for the first time it is Conservative MPs and councillors who are finding it impossible to reconcile “one size fits all” academisation with the rhetoric of increased choice and what Nick Gibb, the schools minister, has called “devolution in its purest form”.

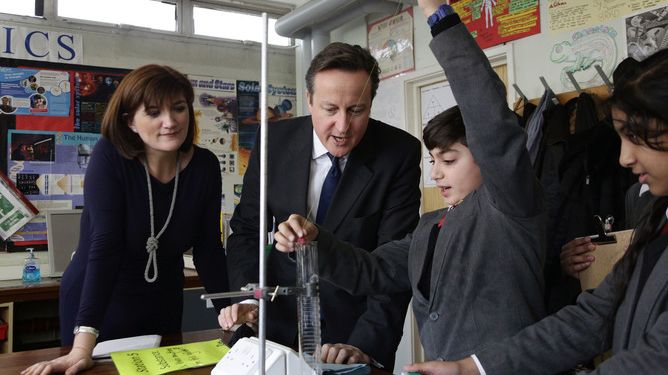

When Nicky Morgan replaced Michael Gove as secretary of state for education in 2014, it was widely reported that her task was to neutralise his “toxic legacy”. At the same time, she continued to implement and extend key policies such as converting schools to academies and tackling so-called “coasting schools”.

Now, her less confrontational approach seems to have become less effective.

The current crisis over academies is taking place against a backdrop of the government’s scrapping of baseline testing for reception children and the National Audit Office’s criticism of the Department for Education’s “inability to provide a clear view of academy trusts’ spending”.

Amid reports that some local authorities may be allowed to get involved in running multi-academy trusts – Morgan told parliament on April 25 that it would be “talented officers” rather than authorities themselves that are involved. But this is unlikely to prevent the same Conservative councillors and supporters from questioning why lots of government money is being spent on complex structural alterations which result in little change.

Academisation has been the central tenet of recent Conservative school policy. Once it begins to be questioned, the foundations of Conservative education policy for over 30 years may start to crumble. In February 2015, David Cameron spoke characteristically intemperately of “waging an all-out war on mediocrity” in schools. As the policy failures mount up, he may now be regretting his choice of language.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Topics

Categories

Northumbria is a research-rich, business-focused, professional university with a global reputation for academic excellence. To find out more about our courses go to www.northumbria.ac.uk

If you have a media enquiry please contact our Media and Communications team at media.communications@northumbria.ac.uk or call 0191 227 4571.